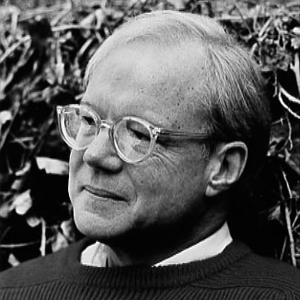

M. Scott Peck

This article was originally published in March 1992.

A candid conversation with America’s all-time best-selling psychiatrist about the joys of love, the evils of Satan and the problem with fidelity

“Life is difficult.”

With those three words, psychiatrist M. Scott Peck began his landmark book The Road Less Traveled and launched millions of personal breakthroughs, religious conversions and psychological catharses. Few books since the Bible have influenced so many people. Certainly, few have sold more. While publishers gleefully celebrate the number of weeks a book survives on the best-seller list, Peck’s book seems to have taken up permanent residence there, going on its seventh year. It has sold about 4,000,000 copies and continues to move at the rate of approximately 500,000 books a year–recently acing out The Joy of Sex as the record holder in the nonfiction category.

In the process, Peck has become perhaps the most famous, and most controversial, psychiatrist in the country. His insights hit home with all age groups, but more interestingly, his infusion of spirituality into psychiatry–a field not known for its close relationship with religion–wins him both admirers, who are looking for moral guidance, and detractors, who find his religious views naïve and puzzling. Three other Peck books have followed The Road Less Traveled onto the best-seller list, and he is a sought-after speaker and lecturer, both as shrink and as religious leader.

Unlike his psychiatrist-turned-writer counterparts who offer self-help, instant therapy and an “I’m OK, you’re OK” view of life, Peck refuses to sugar-coat life’s problems. There are no easy answers, he says. The Road Less Traveled introduces a radically different idea: Of course you’re worried. There is a lot to be worried about.

Millions have found solace in this uncheery thought and in Peck’s prescriptions for coping with today’s harsh realities. For instance, depression, he says, is not necessarily something to be avoided; it is often an appropriate response to change or to the frustration most of us often feel. Nor is it the end of the road; it can be a temporary state in the process of growth. Peck has also sought to redefine our idea of relationships. As long as we hold on to our romantic illusions, he maintains, we will continue to be disappointed and to search for fulfillment in the wrong places. Peck offers no panaceas or quick fixes. He instead advocates hard work, discipline and introspection.

But it is Peck’s concern with spirituality that makes The Road Less Traveled unique. He rebelled against his family’s atheism while a college student, finding solace in Eastern religions well before they were fashionable here. He studied Zen Buddhism and Taoism and practiced meditation but put them aside when he opened his private practice in New Preston, Connecticut, where he was a traditional secular therapist.

“I came to see that psychotherapy and spiritual growth are one and the same thing,” Peck says now. Time and time again, he found that his patients were searching for answers that psychotherapy couldn’t provide. It led him to a search that culminated in his baptism as a Christian in 1980. Unlike traditional psychiatrists such as Sigmund Freud, Peck believes that psychology and religion are complementary. “Theologically, he’s very sound,” says the Reverend William Sloane Coffin, Jr., former senior minister at Manhattan’s Riverside Church.

When The Road Less Traveled was released in 1978, The New York Times summarized it as “psychological and spiritual inspiration by a psychiatrist.” Phyllis Theroux, writing in The Washington Post, called it “not just a book but a spontaneous act of generosity.” In an interview with the Times, she said she was so taken by the book that she spent weeks, “crafting a review for the Post that would force people to buy [it].”

The book, originally titled The Psychology of Spiritual Growth, is a mix of Peck’s common and uncommon sense, case histories from his days of practicing psychiatry, both privately and in the military, and doses of his neo-Puritan philosophy. The publisher, after asking him to rename the book, originally agreed to print only 5000 copies, which quickly sold out. Phenomenal word of mouth–at cocktail parties, group-therapy sessions, A.A. meetings, on college campuses–took over. Peck even received a call from Cher, who had read the book and wanted help from him personally. A year after its publication, it had sold 12,000 copies. In the following years, sales grew, so that by mid-1983–five years after it was released–it crept onto the Times best-seller list for the first time. More than 1,000,000 copies were sold that year.

Peck returned to his typewriter in 1982 and produced an incredibly controversial book, People of the Lie–a study of human evil from that in man-woman relationships to the horror of My Lai. The Wall Street Journal called the book “ground-breaking”; The Washington Times, “a daring study of evil”; and Contemporary Christian Magazine, “one of the most significant new works in recent memory.” This time, Theroux praised Peck’s “act of courage.” Although People of the Lie didn’t come close to the first book’s huge appeal, it was another best seller, as was The Different Drum, which followed. In Drum, Peck moves from diagnosing the woes of individuals to diagnosing the woes of communities, America and the world itself. Subtitled “Community Making and Peace,” the book sets forth Peck’s premise that the human race stands at the brink of self-annihilation and only radically new thinking will save us.

Peck’s background is eclectic. He was born in New York City, where his father; a self-made man from Indiana, had become a successful lawyer and judge. After graduating from Harvard in 1958 with a degree in social relations, Peck bowed to pressure from his father and went into medicine. He enrolled in Columbia University for premed studies and there met Lily Ho, who was born and raised in Singapore. Although his family objected to their interracial relationship, they married a year later.

After receiving his degree in medicine, Peck joined the Army and spent the next nine and a half years as a military psychiatrist serving in Okinawa and the Surgeon General’s office in Washington, D.C. In 1972, he returned to civilian life and moved to Connecticut, where he hung out his shingle as a shrink and worked on his golf game. He, Lily and their three children lived in an 18th Century farmhouse on, appropriately enough, Bliss Road. There Peck led the quiet life of a country psychiatrist until, four years later, he “was called,” as he puts it, to write The Road Less Traveled.

The controversy surrounding Peck’s books and his work–he now spends most of his time lecturing, conducting workshops and promoting his books, as well as writing–continued when his latest book, A Bed by the Window, was released. It is, surprisingly, a novel, but it still provides a forum for his message–this time laced into a mystery about murder and sex in a nursing home. A reviewer for theLos Angeles Times was appalled. “Call me prejudiced! Call me puritanical! Call me naïve! The sex in this novel made my hair curl.” The New York Times, on the other hand, found “this overtly didactic and opaquely religious novel both moving and brave.” The conclusion? Nothing has changed; people are still furiously feuding about Peck, making it high time for us to make our own assessment. Contributing Editor David Sheff, who last squared off with Japan’s controversial politician Shintaro Ishihara, made the pilgrimage. His report:

“Psychologists tell us that everything we do, think and react to has a larger significance. At one time in my life, I thought that was nonsense. I considered most of psychology and psychiatry manipulative, exploitative and even dangerous. They offered panaceas, blame and rationalizations.

“When I first heard about Scott Peck, I was particularly suspicious. The first line of The Road Less Traveled that had been ballyhooed about–‘Life is difficult’–seemed like a less imaginative version of the bumper sticker Life’s A Bitch And Then You Die.

“Then, when my marriage disintegrated, I went into therapy. I came to realize that there was something profound about the process. The motivations for much of what we do are incredibly complex, and it’s no accident that we keep on making the same mistakes. In therapy, I learned that only if we choose to figure out why we do what we do can we live consciously–with our eyes open.

“By the time I was assigned to interview Peck, my mind was open to much of what he talks about, though I remained cynical about his religious references. I certainly appreciated the fact that he doesn’t pretend to have easy answers–and sometimes admits he has none.

“Nonetheless, I wasn’t prepared for the man I met. At times, the interview swung from the sublime to the ridiculous. Peck was full of contradictions. He trembled (attributing the condition to a neurological disorder) and smoked so much that I feel as if the interview had shortened my life.

“We met in Seattle, where he was busy working the talk-show-and-interview circuit to push his novel. After a hearty breakfast of eggs Benedict in the hotel’s restaurant, we moved to Peck’s room for a first marathon session. He sat on the couch, pulling up his khaki slacks at the knees. He adjusted his turquoise sweater and pushed on the nosepiece of his clear-framed spectacles, staring into the coffee he’d made with his travel percolator. His appearance changed with his moods–at times, he seemed older, world-weary; at others, youthful and vibrant. His tone swung from animated to, when he spoke about religion, sex or the demons that he believes exist among us, a barely audible monotone. He rolled his eyes when I asked my more skeptical questions. He’d heard them all before.

“He watched the clocks–three of them were placed around the room–and at precisely five P.M. poured us healthy shots of gin. For all of his solemnness and reverence, Peck was aware that this was, after all, the Playboy Interview. In addition to describing what he likes about our centerfolds (basically, the more provocative the better), he told me a joke for Playboy readers: A very Christian woman with two Christian parakeets went to a pet shop to buy a third but was told that the one parakeet the pet-shop owner had left was inappropriate for her, since the only thing it could say was, ‘I’m a prostitute! I’m a prostitute!’ The woman finally persuaded the man to sell her the bird, anyway–her birds, she said, would save it. So she took it home and placed it in a cage with the Christian parakeets. After a few minutes, the newcomer spouted the only expression it knew: ‘I’m a prostitute! I’m a prostitute!’ The Christian parakeets looked at each other and said, ‘Our prayers have been answered.'”

Playboy: The Road Less Traveled has been on the best-seller list longer than any other work of commercial nonfiction. Why do you think it is so popular?

Peck: People are no longer accepting the answers they’ve been given; they want more. They realize the old program doesn’t work. There’s a larger and larger segment of the population that has made a decision to question the givens–things the culture takes for granted, things people’s parents taught them. They are becoming enlightened. Some go to therapy, some to A.A., some—-

Playboy: Some go to you. How do you feel about the cult that has grown up around you?

Peck: I hate cults. They encourage dependency and conformity, neither of which I believe in. When I get the feeling that there is a Scott Peck cult, I get very uncomfortable. I constantly tell people, “Look, I don’t want to be your fucking Messiah.”

Playboy: Yet you want people to hear your message.

Peck: Well, there is a tendency for us to put people on pedestals. I think that one of our primitive needs is to have heroes rather than to be heroes ourselves. It’s a very odd feeling when people come up to touch my robe, so to speak. Half the time, it’s not all bad. But about half the time, I think, Baah! Ugh! Get away!

Playboy: Before you wrote The Road Less Traveled, you worked as a traditional psychotherapist–a secular therapist. Why did you write the book?

Peck: I was called to write it–that one and each of my other books. They said, “Write me. Do it.” I was under orders.

Playboy: Orders from whom?

Peck: From God.

Playboy: Do you hear a voice or get a feeling? How does God talk to you?

Peck: You know when you are called. The word for it is vocation, which means calling, and is thought to come from God. I suppose it’s a matter of faith, but I believe that some of our drives, our intuitions, do come from God or from Whoever God is–something outside that is wiser, smarter than we are.

Playboy: Were you also called to write your latest book, the novel A Bed by the Window?

Peck: Actually, when The Different Drum was put to bed, it was the first time in ten years that I didn’t feel called to write anything. It felt just great, as if God had let me off the hook. Because I wasn’t writing and had free time, a friend suggested I read some murder mysteries. I took a bunch with me to Jamaica.

Playboy: Anything in particular?

Peck: I can’t even remember. All I know is that I was going to Jamaica to play golf, even though I was getting all sorts of messages that I was overdoing it as far as my bad back was concerned. I was reading these mysteries, too, thinking it would be fun to try to write one. Then I threw my back out and was stuck on my back in Jamaica with nothing to amuse me except a Dictaphone. I said to myself, My God, what am I going to do for the next two weeks, other than pray? I started dictating the book. It just clicked and said, “Write me.”

Playboy: The Road Less Traveled is famous for its opening sentence, “Life is difficult.” Why do you think that’s such a provocative idea?

Peck: Well, the most common response I’ve gotten to my books has been not that I’ve said something radically new but that I’ve said the kind of things that people have been thinking all along but are afraid to talk about. Well, life is difficult.

Playboy: Yet the pervading sensibility in our culture is “Don’t worry, be happy.”

Peck: We’re supposedly a Christian culture, yet Jesus wasn’t terribly happy. He never had much peace of mind. The common image of him that Christians try to create is what my wife, Lily, calls the wimpy Jesus–someone who went around with this sweet smile on his face, doing very little other than patting children on the head. But that’s not at all the Jesus of the Gospels. The fact is, life is difficult and there is often much to worry about. That’s very disillusioning for people who think that we’re here to be happy.

Playboy: Why are we here?

Peck: To learn. In my gloomier moments, I think this is a kind of celestial boot camp. Children are done a disservice if they are taught that they ought to be happy. They are in for great disappointment.

Playboy: Don’t your patients go to you because they want to be happy?

Peck: I used to tell my patients that therapy is not about happiness, it is about power. I can’t guarantee that you’ll leave therapy one jot happier. What I can guarantee is that you will leave more competent. There is a certain joy that comes from knowing you’re worrying about the big things and no longer getting bent out of shape over the little ones.

Playboy: Do shrinks—- Excuse us, do you object to that word?

Peck: I don’t care, but the idea of head shrinking has to do with people’s anxiety. In fact, psychotherapy is about the opposite: It is headexpanding, consciousness expanding.

Playboy: Why are people so anxious about therapy?

Peck: They can’t handle the paradox that both the sickest and the healthiest go into therapy. To be in therapy suggests to some people that you are nuts, whereas it often means you are far healthier than many people who stay away from therapy.

Playboy: Resorting to therapy is also sometimes viewed as a weakness in a culture that places a high value on being able to handle problems by ourselves. Going to therapy means admitting that you need help.

Peck: In fact, it is often the wisest people who realize when help is necessary. I believe that therapy can benefit almost anyone willing to dedicate himself to it. Some people certainly do fine without it, but many others find themselves making the same mistakes over and over. Usually, they’re looking for the reason for their problems everywhere but where it lies. Therapy is the only process devoted to finding the source of those problems and changing it.

Playboy: Psychology and psychiatry are not exact sciences, so it’s difficult to determine what effect they have. How can you tell if you’ve helped a patient?

Peck: There was one study in which researchers took one group of people and put them into therapy, while refusing therapy to a control group. Three or four years later, they found that the patients who hadn’t had therapy were just as healthy as those who had. However, about ten years after the study, somebody decided to look again. They found that there was a remarkable difference between the treated group and the untreated group. The group that had had therapy had more variability. Some were far more healthy, and some were far more unhealthy than they had been.

Playboy: What do you conclude?

Peck: Well, they traced it further to particular therapists. Good therapists made people better. Bad therapists made people worse.

Playboy: Which brings up a major question: How does one choose a shrink?

Peck: I get so many letters asking how to choose a therapist. All I can say is, don’t hesitate to shop around. Go on your gut feelings. Different styles of therapy are appropriate for different types of people. When I went into therapy, I was already clearly aware of some spiritual parts of my nature, so I went looking for a Jungian therapist. I found one, and I was furious because he kept treating me as if he were a Freudian–after our first session, he didn’t say anything for the next eight sessions. I never learned anything about his personal life. I kept taking in these beautiful dreams and I waited for him to analyze them, but he never said a word about them. Well, it took a long time for me to realize that his silence was exactly what I needed. You begin to know after you have been in therapy for about three months. You may not feel any better, but you may have some sense that the process is going in the right direction, that it’s a process that you need. If by the end of three or four months you don’t have that sense, I would question whether you ought to work with somebody else.

Playboy: Some people claim that many shrinks are more screwed up than the people they treat.

Peck: It’s not that simple. I’ve known some therapists who were quite screwed up but who were extremely good.

Playboy: Another confusing aspect of therapy is the number of philosophies it embraces–Freudian, Jungian, Gestalt, and so on. To which do you subscribe?

Peck: To none and to all. The best therapists are invariably eclectic. If I could take only one school of thought to a desert island, I would take Freud’s. He was a true genius. He had no peer. Unfortunately, he gave psychotherapy a serious antireligious bias.

Carl Jung was helpful in starting to correct that. His chief contribution was to bring spirituality into psychology. Maslow brought spiritual aspects to therapy; he also brought the idea of studying healthy people. And he found, by the way, that the healthiest people tend to be quite spiritual. Adler founded the social-work movement and emphasized power and will, which have remained neglected subjects. Each school essentially describes a piece of a person. I think we need pioneers, founders of new schools.

Playboy: How do you feel about alternative therapies–from Werner Erhard and est to primal scream?

Peck: Anything carried to an extreme can cause harm. Est became a cult. Cults are dangerous.

Playboy: What about radio and TV shrinks–such as Toni Grant and Dr. David Viscott?

Peck: I haven’t listened to any of them. However, in the book-promotion business, I do call-in shows, and I’ve gotten a taste of what those media therapists do. I used to think, God, no, I can’t do that. But now I think it’s OK. It’s amusing.

Playboy: Do media therapists help people?

Peck: I think they probably would have been sued up the kazoo and put into jail if they had done harm. But, generally, no, I don’t think anybody gets real therapy over the phone. The best help a media therapist can probably give to someone with a real problem is to recommend that he or she see a therapist for real therapy.

Playboy: Are you supportive of other pop trends in psychology?

Peck: You know what I am critical of? I am a critic of the critics of psychologizing America. Plato said that the unexamined life is not worth living. Well, more and more people are examining their lives. That cannot be bad.

Playboy: Some therapists break completely from the Freudian model and become part of their patients’ lives. You even hear about therapists who seduce their patients.

Peck: Of course there are people who abuse the relationship. I think it is generally best for a therapist to keep his distance from a patient, but all rules are made to be broken. I think we should be nervous about breaking rules.

Playboy: Have you broken rules?

Peck: With the exception of sleeping with a patient, I’ve probably broken each of those rules. When I look back, I think I significantly helped a small portion of my patients, but I don’t think that I’ve harmed any of them. There were times when I found it was appropriate to talk about my own life in therapy, which is generally viewed as verboten, and there were some times I made that decision wrongly.

Playboy: How do you feel about the charge that psychotherapy is elitist–that many people can’t afford the money or the time to indulge in it?

Peck: That’s a concern but not a significant one. Decent therapy is available to almost everyone. There are sliding fee scales, free clinics. The more likely scenario is that people who need therapy find excuses not to go.

Playboy: But do you acknowledge that therapy is more of an option for the upper and middle classes than for the lower classes?

Peck: Ordinary therapy is not going to work in a culture of poverty, where there is so little capacity for delaying gratification. You have to have a tremendously large ability to delay gratification to get anywhere. There is no instant fix. You have to pay your bills.

In my own practice, no matter where patients fell on a sliding scale, when they would bounce checks, I would practice what I call checkbook therapy. Learning how to balance one’s checkbook is a first step in being responsible for other aspects of one’s life. That’s one of my concerns about this country. I’m concerned about how much this country has to grow in health when it can’t even balance its own checkbook.

Playboy: You’ve said that the success of The Road Less Traveled is connected to the proliferation of groups such as A.A. Why are A.A. and its offshoots so popular?

Peck: I believe, along with many other people, that perhaps the greatest event of the 20th Century occurred in 1935 in Akron, Ohio, when A.A. was established. A.A. was the beginning of the self-help movement, and also the beginning of the integration of science and religion on a grass-roots level.

Playboy: Why does A.A. work?

Peck: When I was studying psychiatry, it was assumed that A.A. worked with alcoholics–better than psychiatry did–because alcoholics were what we called oral personalities who got together at A.A. meetings and yapped a lot, smoked a lot and drank a lot of coffee and in that way satisfied their oral needs. Most psychiatrists still think A.A. is a substitute addiction. But that’s a bunch of shit. A.A. works because it’s a program of religious or spiritual conversion. I suspect that many people who do not profess to be religious have a sense of a higher power, even when they’re not yet on friendly terms with it, and A.A. helps them discover that. It works because it’s a psychological program that helps uncover the motivations behind unhealthy symptoms. It teaches people not only why they should go forward through the desert toward God but also how they should go forward through the desert. It teaches people how to support one another. Joining A.A. is obviously not an easy decision. When you have made the decision, there is some sadness in being in this minority who have transcended the culture. [People in A.A., therapy, etc.] make up four or five percent of the population now, which is significant.

Playboy: In what way?

Peck: The bigger the number, the more we can go forward as a race.

Playboy: How so?

Peck: We take control of our own lives and become intolerant of irresponsible governments. People become more compassionate and at the same time more competent. Being awake involves an appreciation of life, of the environment, of our fellow man. And an intolerance of waste, of incompetent bureaucracy, of prejudice….

Playboy: And you believe A.A. has significance beyond the treatment of addiction?

Peck: Yes, because it teaches people about community.

Playboy: On a larger scale, what implications could it have?

Peck: My wife and I started The Foundation for Community Encouragement, with the idea of incorporating A.A.’s way of thinking. It’s a nonprofit educational foundation with the goal of teaching individuals, groups and organizations to communicate, deal with difficult issues and overcome their differences to form communities. We have workshops in which we teach groups how to make decisions by consensus–instead of by fiat or by vote. People learn to trust that process.

Playboy: Can you give a practical example of how that process works?

Peck: I guarantee you, if you can get, let’s say, five Anglos, fifteen Afrikaners and thirty-five blacks together in South Africa in the same room for three or four days, willing to go through our process, they will come out not only loving and respecting one another but able to work together with phenomenal efficiency. The problem is getting them into the room. The potential for conflict resolution is enormous. Do that with groups inside cities. Or with factions in government. When we conduct our workshops, people who thought they could never agree are amazed. It gets to the point that they want to know if they are hooked on the foundation to help them solve their problems.

Playboy: Well?

Peck: The answer is no. It’s the same answer I give to people who want to know when they should stop therapy.

Playboy: Which is?

Peck: When you become your own therapist, therapy becomes a way of life. The same for groups–you don’t need the foundation once you’ve learned to do it yourself and it becomes a way of life.

Playboy: What about one of the latest trends in pop psychology, codependence? More and more people are convinced that theirproblem is that they put someone else’s problems before their own. Al-Anon, the A.A. offshoot for families of alcoholics, is increasingly popular. Why is codependence such a popular problem all of a sudden?

Peck: The problem isn’t new, only the word. Do you know how many Al-Anon members it takes to screw in a light bulb? None. They just let it screw itself in. Do you know the last thing a codependent sees before he dies? Somebody else’s life flashing before his eyes.

Anyway, for longer than it has been trendy, I’ve given a lecture about the togetherness and the separateness in marriage and families. In order to live well, we have to negotiate a kind of tightrope between these two extremes, to have X amount of togetherness and X amount of separateness. When Lily and I were doing therapy with couples, we more often than not found couples who were too much married.

Playboy: Does that mean they spent too much time together?

Peck: Beyond that–they had come to make up one person. In groups, we found we had to separate husbands and wives, put them in different parts of the group. Still, we’d ask John what he thought about something and Mary would answer, “John thinks this way.” The same thing would happen when we’d ask Mary.

The same thing is true of children. Ultimately, the task of parents is not to keep the family together but to help your children separate from you. One of the things that confused me early in my psychiatric career was discerning a pattern for children leaving home: Those who grew up in warm, nurturing, loving homes usually had relatively little difficulty in leaving those homes, while children who grew up in homes filled with backbiting, hostility, coldness and viciousness often had a great deal of trouble leaving. It seemed to me that if you grew up in a warm and loving home, you’d want to stay there, and that if you grew up in a home full of hostility and hatred, you’d want to get the heck out as soon as you could. But I came to realize that we tend to project onto the world what our early childhood home is like. Children who grow up in nurturing homes tend to see the world as a warm and loving place and say, “Hey, let me at it.” Children who grow up in a home filled with hostility and viciousness tend to see the world as a cold, hostile and dangerous place.

Playboy: What kind of therapy helps those children?

Peck: It’s all about reprogramming the tapes–the internal and external tapes. This supposedly Christian culture emphasizes family values–the family that prays together stays together–as if Jesus had been some kind of a great family man. I don’t necessarily want to knock family values, but the fact is that the Jesus of the Gospels was not a great family man. If anything, he was a breaker-up of families. He set siblings against siblings and children against parents. And he did that because he was fighting against the idolatry of family–where family togetherness becomes sacred at all costs, where it becomes more important to do what will keep the family matriarch or patriarch happy than to do what God wants you to do.

Playboy: Is that your objection to couples who are “too much married”?

Peck: No. When we look to a spouse or a lover to meet all of our needs, to fulfill us, to bring us a lasting heaven on earth, it never works, does it? It’s very natural for us to want to do that, because it’s natural to want to have a tangible God, one we can touch and hold and embrace and sleep with and maybe even possess. But it doesn’t work.

Playboy: How do you help couples avoid that trap?

Peck: I’ve said before that there are only two valid reasons to get married. Lots of invalid ones but only two valid ones. One is for the care and raising of children. The only other valid reason is for the friction marriage provides.

Playboy: Friction? Well, then, most marriages are probably doing fine.

Peck: [Laughs] A marriage ought to consist of two people who are gathered for some purpose higher than that mere pleasure of being together. Namely, to help each other on their own journeys of spiritual growth, through and with the friction.

Playboy: That’s hardly romantic.

Peck: People have the fantasy that once they get married, they will no longer be lonely. Then, when they find themselves still lonely, they think, Well, gee, the marriage must be bad, it must not be working. But the healthiest marriages can, at times, be lonely places. The answer is learning and growing, and your marriage can help you do that.

Playboy: How?

Peck: First, examine it and yourself. A woman went to a therapist because of headaches that her regular doctor told her were not physical. She said, “I don’t know why I should have psychosomatic headaches. Everything is wonderful in my life. I’ve been married for four years now and my marriage is absolutely glorious and my husband is a saint.” Then therapy starts and, of course, in very short order, she acknowledges that her husband maybe annoys her a little bit, then that things he does really bug her and that, as a matter of fact, she really can’t stand certain things about him. And the woman comes to the terribly painful realization that she and her husband have fallen out of love. Suddenly, the headaches go away.

Playboy: So the headaches are cured, but the marriage is in serious trouble.

Peck: The marriage was obviously in serious trouble, anyway. Denial seldom works for long. What often happens is that couples fall into a pattern of dominance and submission. One partner is the dominant partner–in about two thirds of the cases it’s the male–and the other is the submissive partner. You can obviously avoid friction if one person is accustomed to and comfortable with giving all the orders and the other person doesn’t mind taking all the orders. But it’s not particularly good for people’s spiritual growth to live their lives in those roles.

Lily and I fell into it before our marriage, when we were engaged. I was the dominant one and she was the submissive one. But typically, after about five or six years of marriage, couples become sick of that pattern. The dominant member becomes sick and tired of the submissive member’s being defendant all the time, and the submissive member becomes sick and tired of being bossed around. They start trying to renegotiate the power structure of the marriage. When it cannot be renegotiated, couples split up. That is one of the major causes of divorce between five and ten years.

Playboy: Is that what the seven-year itch is all about?

Peck: Yes. It is being discontented with the given order and accepting it as unchangeable. Often, there is an illusion, a delusion, that a new partner will solve the problem.

Playboy: What is the alternative?

Peck: Healthy couples renegotiate the power structure. At about the five-year in mark in our marriage, I grew sick and tired of Lily’s dependency and she grew sick and tired of my being a male chauvinist pig, which I was, so we began to try to renegotiate. That involved, among other things, going into therapy. We worked hard and still work hard on it.

Playboy: As an alternative to traditional talk therapy, more people seem to be relying on drugs–Lithium or antidepressive medications. Where do you stand on the drug- vs.. talk-therapy debate?

Peck: When I practiced, my specialty was not biological psychiatry, but I would still use some phenothiazines for the few schizophrenic people I saw and, more commonly, I would prescribe antidepressants. Sometimes, people aren’t even ready to participate in therapy, because they’re so depressed they can’t participate unless you give them some drugs. The problem is getting people to tolerate the side effects.

Playboy: One study has suggested that a startling number of Americans–at least ten percent–suffer from undiagnosed depression. Do you agree with that figure?

Peck: One hundred percent of people suffer from depression, including me.

Playboy: Clinical depression?

Peck: First of all, suffering from depression isn’t a bad thing. There is a section in The Road Less Traveled on the healthiness of depression. One of the benefits of being a religious person is that other people just get ups and downs in their lives, and we get to havespiritual crises. It’s much more dignified to have a spiritual crisis than a depression. And, I suggest to you, you’ll probably get over your depression quicker if you look at it as a spiritual crisis, which it usually is.

Playboy: Or, if you’re right about drugs, a biological crisis.

Peck: For some people, it is primarily a biological crisis. In most, it’s mixed. It depends on the severity and duration of the depression. But depression is a problem for everybody.

Playboy: When you talk strictly about psychology, you are aligned with many others in your profession. But when you bring in religion and spirituality, you alienate many of them. What do you find lacking in secular psychology?

Peck: To me, religion and psychology are not separate.

Playboy: Yet, as you admitted, psycho-analysis’ roots are antireligious. Is that antagonism toward religion based on the fact that religion offers answers outside oneself; psychology, inside?

Peck: I think the reason psychiatrists are against religion is different. Freud, the granddaddy of American psychiatry, was an atheist. Also, he wrote in the heyday of the scientific movement, at the turn of the century, when the world was considered a materialistic place that could be understood in materialistic terms. That attitude has altered dramatically with the new discoveries in physics. And psychiatry was largely a Jewish profession. I would estimate that probably sixty percent of psychiatrists in the country are Jewish. That’s certainly a reason psychiatry would be anti-Christian.

Playboy: But not antireligious.

Peck: Well, psychiatrists also tend to see the casualties of religion, which gives them a biased outlook. We see people who have been hurt by those rigid, frigid nuns and we tend not to see the people who have been saved by those rigid, frigid nuns.

Playboy: Saved? By nuns?

Peck: I don’t mean religiously saved. I mean people who grow up in chaotic, homes but, in that rigid parochial school, learned some principles that allowed them to escape their background.

Playboy: Psychiatry teaches people to live consciously. Religion implies a degree of simple faith. Psychiatry holds that we’ll get further relying on critical thinking than on faith, doesn’t it?

Peck: But if you’re going to be a real good doubter, after a while, you have to start doubting your own doubts.

Playboy: But doubting doesn’t necessarily lead to religion.

Peck: Part of my own religious development actually came about through my psychiatric work. My interest was in long-term psychoanalysis devoted to substantial personality change, not in superficial answers to problems. One of the things I found after a few years was that many of my patients would go into what I call a therapeutic depression. This would usually occur between the first and second years of therapy, and they would become far more depressed than they had been when they came in to therapy.

I realized that what happens is that the patient’s old way of being is no longer tenable for him. Such patients become conscious enough to see clearly how stupid and maladapted and sick that old way is. But rewriting the tape seems so difficult, so risky, that they feel they can’t go either backward for forward, so they say, “Why don’t I just go sideways? Why don’t I just kill myself? Grow? Grow toward what? Why not just give up?”

These are questions that are not even raised, let alone answered, in textbooks on medicine or psychiatry. These are spiritual questions.

Playboy: They are raised in traditional psychotherapy. That’s the time the patient makes choices and rewrites the tape consciously.

Peck: Well, in my case, people asked me seriously, “Why should I grow?” or “Why shouldn’t I kill myself?” I had two ways to respond. One was to shrug my shoulders and say, “Golly, gee, I don’t know why you shouldn’t kill yourself.” The other was to get down with them and wrestle with the spiritual issues.

Playboy: Another therapist would help them figure out why they shouldn’t kill themselves. Isn’t the point of psycho-analysis to reach that pain?

Peck: In People of the Lie, I wrote, “Faith is the choice of the nobler alternative.”

Playboy: Do you believe faith is a choice?

Peck: Half choice, half gift.

Playboy: It doesn’t feel like a choice to someone who sees a fallacy behind it.

Peck: He has the choice of doubting his own doubts.

Playboy: That’s what therapy is about.

Peck: And if you do that well enough, you may come to something. To me, there are three approaches to human meaning. One is called nihilism, which assumes that there is no meaning and, consequently, it doesn’t matter what the fuck you do. Then there is what I would loosely call existentialism, which holds that there’s no reason to conclude that there is any meaning to life, but to live as if life were meaningless is too horrible and too destructive to consider.

Playboy: Existentialism can lead to a choice that life has the meaning we give it, which is different.

Peck: Only because it’s intolerable for it not to have meaning.

Playboy: No, but because that is life’s meaning–the choices we make, our roles as children, friends, parents….

Peck: Well, the third position is what I adhere to–that life actually does have meaning, and part of the reason we’re here is to try to figure out what the meaning is.

Playboy: There’s no real contradiction between that and existentialism–it’s semantics. Life inherently has meaning and we choose to define what that is.

Peck: That is the problem with secular humanism, basically that position. It maintains that we could be our own creators. I don’t think we’re that smart.

Playboy: Just because we’re not that smart, why presume someone else is?

Peck: My experience is that I am being manipulated by a power beyond me. I think many people have that experience. What some people do is to ignore it. I choose to cooperate with it, because as far as I can ascertain, this manipulative power is infinitely more intelligent than I am and seems to have my best interests at heart. That doesn’t mean I’m powerless, but I see us as being co-creators. For me, that makes more sense than secular humanism, which says that we create everything, or some kind of Calvinism, which says that God predetermines everything.

Mental health is dedication to reality at all costs. If you’re willing to be dedicated to reality at all costs, you’re going to have experiences that will lead you to question the rational, purely physical stuff. My primary identity is as a scientist, even before that as a religious person. We scientists are empiricists, meaning that we think that knowledge comes primarily through experience. I’m reminded of Carl Jung. Just before he died, he was captured on film. In the interview, he was asked if he believed in God. Old eighty-three-year-old Jung puffed away on his pipe. “Believe in God?” he said. “Believe is a word that we use when we think something is true but for which we do not have any substantial body of evidence. No, I don’t believe in God. I know there is a God!”

Playboy: Do you believe in reincarnation?

Peck: For the most part, I am very leery of any doctrine that can be used to explain away the mystery of life. Some people who buy reincarnation say that children choose their parents. I am sorry, but I’ve seen children born into homes where their souls have been systematically diminished. While it may be necessary for us to go to the cross in adulthood, I know of no law that would cause a child to be born into a home where his soul would be systematically diminished. Karma or your moon being in Aquarius can be used to explain everything. My variety of Christianity is not used to explain everything. It accepts and appreciates mystery.

Playboy: Yet even within the Christian community, you are controversial.

Peck: I think the people who object to me are on the fringes. I get some opposition from what might be called far-right-wing Catholics and some opposition from the far-left-wing or New Age religious people and a lot of opposition from the fundamentalists.

Playboy: But you’ve described yourself as a fundamentalist.

Peck: I dislike the term fundamentalist. Fundamentalism began simply as a movement to get back to some of the basics of Christianity, but the term got taken over by fanatic Christians. I’ve been picketed twice. People have handed out leaflets saying that I’m the Antichrist. That’s real power–I mean, not one of the antichrists, but the Antichrist. The patterns of opposition are sometimes quite fascinating. At our foundation workshops, we have as much of a problem with the New Age fundamentalists–who insist not only that there be herbal tea present but that everyone drink it–as we do with Christian fundamentalists.

Playboy: Why do you object to the New Agers?

Peck: A very popular New Age book is Love Is Letting Go of Fear, by a psychiatrist, Jerry Jampolsky. It’s about forgiveness, which is a terribly important topic.

But the problem with the book is that it’s very simplistic. It makes forgiveness sound easy, which it isn’t. The New Agers seem to think you should just beam the affirmations out there. That’s the kind of New Age Christianity I have a hard time with. It’s not about reality. One New Age joke that was given to me, appropriately, by a New Age woman goes like this: Three ministers are down in hell–a Catholic priest, a Jewish rabbi and a New Age minister. The topic of the conversation turns to why they’ve ended up in hell. The Catholic priest says, “Back on earth, I just loved booze too much. That’s why I’m here.” The rabbi says, “I had this thing about ham sandwiches. I just couldn’t leave them alone.” They turn to the New Age minister and ask, “How about you? What are you doing down here in hell?” The New Age minister replies, “This isn’t hell and I’m not the least bit warm.”

Another thing about the New Age movement I object to is its reaction against technology. Science is very holy. The scientific method consists of a bunch of conventions and procedures that we’ve developed over the centuries in order to combat a profound tendency we humans have to deceive ourselves. It’s the search for the truth.

Playboy: And a contradiction, ultimately, to religion.

Peck: A complement to religion. God is love, God is light, God is truth. And so science is very godly. But it doesn’t answer all questions. And that is one of the things that characterize the New Age movement–a lack of skepticism or discernment. Before I’m going to shower with crystals, I want to investigate whether or not crystals improve health.

Playboy: Why is the New Age movement so popular? Is it simply a reaction against traditional religions?

Peck: That’s exactly the right word–reaction. It is a reaction against the sins of Western religion and the sins of science, or at least as they’ve been translated into technology. It is looking for new ways.

Playboy: Why do you oppose that?

Peck: Well, as such, it is potentially very holy. I think the sins of the Christian church have been enormous and they should be reacted against. But the problem with the movement is what we call reaction formation, in which you go to the other extreme and throw out the baby with the bath water. I’ve done that in my own life. My father, who was a longtime judge and a famous litigation lawyer, had a fair amount of anger. He would sometimes go off in an inappropriate tirade, directed either at us children or at somebody else–some hapless desk clerk or bus boy. Once, when I was twelve or thirteen and we were traveling, I remember squirming in the middle of one of those public outbursts and thinking, When I grow up, I’m never going to make an ass out of myself like that. So when I grew up, I never got angry in public. Only I had high blood pressure, and people started calling me aloof and cold and distant. I gradually realized, at the age of thirty or so, that I had thrown the baby out with the bath water, that I should have gotten rid of inappropriate anger in public, not of anger in public.

Playboy: What babies are the New Agers throwing out with their bath water?

Peck: Christian theology, which is probably the best theology we’ve got. They react against how Christians have behaved, not what they’ve believed. As G. K. Chesterton put it, “The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting, it has been found difficult and left untried.”

Playboy: Since mankind has such a difficult time not perverting dogmas that may, indeed, be pure, perhaps it’s not so bad to throw them out.

Peck: Well, it happens, that’s for sure. Religions are usually started by very holy people–say, Buddha and Jesus and Lao-tzu. One of the greatest mystical writings in the world is the Tao Té Ching. My fantasy was, “Boy, these Taoists really have it together.” Well, if you go to Taiwan and see Taoism being practiced, you see that it has degenerated to a bunch of magical hodgepodge. Same with Buddhism. And Christianity.

Playboy: Do you believe in faith healing, or at least that there are psychological factors in sickness and healing?

Peck: I believe there’s an enormous amount to it. A great many diseases are psycho-socio-spirituo-somatic. I’ve known of some cases of cancer in which it has been indelibly clear that the victim has reached a dead end in his or her life. I’m not saying that all cases of cancer are like that, but there is no question in my mind that virtually all diseases have some psycho-socio-spirituo-somatic components.

Playboy: Do you believe that patients can help heal themselves through visualization techniques and other kinds of meditation?

Peck: I know that the mind has a role in illness. In one study, a group of cancer patients was given group therapy along with their treatment and another group was not. The doctor’s idea was not so much to affect their health as to give them comfort and support. What he found, though, was the cancer patients in group therapy lived significantly longer than the others.

Playboy: Do you believe there is an emotional component to AIDS?

Peck: I get the impression that the fact that somebody is exposed to AIDS doesn’t necessarily mean he will get it. There is a new field on the cutting edge of medicine called psychoneuroimmunology. It studies the way our psychology can affect our immune systems. About six years ago, I almost died from pneumonia. I was working this insane schedule, so I was physically fatigued. I hadn’t come to terms yet with my limitations. My book had just hit the best-seller list a few months before. I was dealing with the problems of fame. There were some people who wanted me to run for President. I was taking that notion seriously at the time. I picked up a bug from my son, who had pneumonia. There was psychological and physical stuff going on. It was probably both of those.

Playboy: If you hadn’t been ill, perhaps we’d have had a different President.

Peck: I doubt that. I decided that I was constitutionally unqualified, and not by the U.S. Constitution but by my physical constitution.

Playboy: How serious were you about it?

Peck: Well, after about two years of people’s telling me that I should, I began to take it pretty seriously. But when I realized I could never emotionally or physically handle the job, I began to wonder how any sane person could be qualified.

Playboy: Could someone with your religious convictions be elected?

Peck: I think people would like to see genuine spiritually reflected in their leaders. That includes genuine morality.

Playboy: Did your religious sense come from your family?

Peck: Our home was secular, but I was curious about religion. In school, I took a course in world religions and fell in love with Hinduism and Buddhism. They made sense to me. When I was eighteen, I was a Zen Buddhist–way before it was fashionable. I became a Christian as I wrestled with the ideas of sin and guilt, remorse and contrition. Christianity dealt with those in ways I felt made sense.

Playboy: How did you end up in psychiatry?

Peck: The only time my father advised me correctly was when he suggested I go to medical school.

Playboy: He was a lawyer. Why did he suggest medical school?

Peck: Because I’d majored in psychology, and he knew that I was so antipathetic toward him at that time that I would never be a lawyer.

Playboy: Did you go into therapy?

Peck: In the military, where I took my residency, I worked in a hospital and a clinic. I went into therapy for the last year of my residency, not because it would be a learning experience but because I needed it.

Playboy: Is it possible to sum up what you got out of therapy?

Peck: I think the biggest single thing that I learned was that among other problems that I had at the time was a profound one in dealing with authority. Whenever I studied or worked, there was always some son of a bitch in charge whose guts I absolutely hated. It was always a man, always an older man, a different man each place, but wherever I went, that man was there–which I assumed was hisfault and had nothing to do with me. At the time I went into therapy, if you’d asked me whether I was a dependent sort of person, I would have said, “Scott Peck doesn’t have a dependent bone in his body.” I discovered that my problem came from my father. He was an extremely attractive figure, very bright and very loving in his own way but also the most overcontrolling character who ever came down the pike. If he could have, he would have controlled not only what college I went to but what I majored in and what graduate school I went to and whom I married.

When I was a child, he was somebody I’d have liked to depend upon, but to depend upon my father would have been to be steam-rolled by him. To preserve my identity, I had to keep my distance from him. The way I did that was by saying, Who needs him? Who the hell needs anybody? I think my therapy was helpful in a whole bunch of ways, but one was in putting me in touch with my dependency needs.

Playboy: So all those bad generals were bad fathers?

Peck: Yeah. I was looking for the ideal father figure. But since I didn’t know I was dependent, I wasn’t even aware that I was looking for a father figure. When these men would fail to be ideal father figures, I’d get furious with them. After analysis, I felt, This guy is not my ideal father, so I’ll take what I can from him.

Playboy: Where did you meet your wife?

Peck: I sat behind Lily in a class one summer. Every morning, I looked at the back of her neck. Perhaps I’m a nape man and don’t know it. Also, perhaps I was attracted to her because she was Chinese and had sort of an exoticness. We married thirty years ago, practically over our parents’ dead bodies.

Playboy: Because of the difference in your races?

Peck: My parents raised me to be the ultimate WASP. I was marrying a chink. They told me I was ruining my life, that I’d have no friends. They disinherited me. Her parents were equally bad. They were furious because they had lost control of her.

Playboy: Was it difficult for your kids?

Peck: It was harder on them than on us. They encountered prejudice in school. But it turned out well, I think. They are very strong people.

Playboy: You have admitted that you were not as good a father as you should have been because of your calling.

Peck: Well, I had no trouble changing my children’s diapers or any of that. But I was very impatient with them from about the age of two until they started becoming interesting to me at about thirteen. I didn’t spend time with them. If you asked them, “What kind of father was your father?” they’d say, “Well, he was pretty good in a crisis, but you had to have a crisis to get his attention.”

Playboy: Do you regret that?

Peck: I wish I’d had been a better father, yes. I wish I’d had more time for them. I’m grateful that we have good relationships now.

Playboy: Why did you become a military psychiatrist?

Peck: Well, it was an odd choice. Years before, I’d actually been one of the first R.O.T.C. protesters against the military. I got kicked out of Middlebury College for it. That was back when McCarthy had not been long dead, which tells you about the era. Well, although it wasn’t announced in the school catalog, Middlebury had a compulsory R.O.T.C. course. I objected, so in the middle of my second year, I stopped going. They docked all my academic credits. Fortunately, because my father was on the alumni council, Harvard admitted me and restored my credits.

Playboy: Then how did you end up in the military?

Peck: After I graduated from medical school with two young children, the military was the only place I could get decent training and a livable wage. I looked back at my experience with the R.O.T.C. and said it was just my adolescent rebellion. About two and a half years later, partly through a couple of my patients, I began to wonder about the Vietnam war, and then I looked further into it. Finally, I realized, My country is lying so badly there is no way to rationalize it. I realized that our involvement there was evil.

Playboy: Yet you stayed in the military for several more years.

Peck: I used my position in the military to study what was really going on. The more I saw, the more I was faced with a question. I wondered whether or not I should go to jail. I looked into the people who had abrogated their military commitments and been sent to jail. Well, their voice was lost. It didn’t seem to me a terribly responsible thing to do, with a wife and two children.

Playboy: The voice of those who went to jail was not lost; it made a strong statement.

Peck: Maybe it was a cop-out, but I decided to be one of those people who worked from within. That was how I started really becoming interested in the relationship between psychiatry and politics and government. That was why I stayed in the military longer than I had to and gave up a very lucrative Harvard fellowship to stay in the Army and go to Washington. I learned a lot.

Playboy: And did what with it?

Peck: I was in the Surgeon General’s office. From that position, I leaked information to [columnist] Jack Anderson’s people.

Playboy: Specifically, what?

Peck: There were many things I considered to be scandals that I kept Anderson’s office apprised of. But eventually, I got disillusioned and tired and quit. That’s when I went to Connecticut, with no greater ambition than just being an ordinary country psychiatrist and getting to play golf on weekends and Wednesday afternoons.

Playboy: You say you came to believe our involvement in Vietnam was evil. What’s the background of your research in evil?

Peck: The book and the movie The Exorcist first piqued my curiosity about possession, though I thought they did the subject a disservice by being simplistic. The girl became possessed for no reason, as if possession were some kind of accident. That could lead people to think that you could be walking down the street and a demon might leap out from behind a bush and dive into you.

Playboy: It wouldn’t?

Peck: In fact, there are profound reasons why people become possessed.

Playboy: You’re serious?

Peck: Quite serious.

Playboy: And you actually believe in the Devil, not a metaphorical Devil but a real Devil?

Peck: I didn’t always. After reading The Exorcist, the next thing I read on the subject was Malachi Martin’s Hostage to the Devil. While I think it is overdramatic in some ways, it has a sufficient smack of reality to say to me, “Hey, maybe I have to take this thing seriously.” One of the things that Martin makes clear is that possession is not an accident. There is, in every case, what he calls cooperation.

Playboy: And do you maintain that making a pact with the Devil is a psychological disorder like schizophrenia or mania?

Peck: Yes, though possession is a rare disorder.

Playboy: Isn’t someone who acts possessed simply psychotic?

Peck: The two patients I worked with were not in the least psychotic, though one was able to fake psychosis.

Playboy: What’s the difference, as far as symptoms are concerned?

Peck: Someone who is truly insane cannot pull himself together. But just an in some ways people who are possessed have chosen to cooperate with the demonic, exorcisms succeed because they can reverse the choice. That’s the essence of exorcism.

Playboy: Do you believe that a physical spirit actually enters someone’s body?

Peck: This gets very hairy. Satan is a spirit–it doesn’t have horns, hooves and a forked tail. But Satan has no power except in a human body.

Playboy: Can you give an example of possession?

Peck: I had two patients who were possessed. I once attended an exorcism.

Playboy: A real exorcism.

Peck: Yes, during which the patient had to be restrained because she was violent much of the time. She would often lie face down on the bed to try to escape. You could lay books on her and she would just lie there quietly. But when you put the Bible or The Book of Common Prayer on her, she would start to writhe.

Playboy: You actually put prayer books and Bibles on her back?

Peck: Yes.

Playboy: And you consider that proof that she was possessed, not simply nuts? It sounds like proof that you were nuts.

Peck: [Smiles] Well, there were other things that were much more compelling. The most compelling thing for me was her facial expressions. I mean, they blew my mind.

Playboy: You couldn’t compare them with those of someone who was having another kind of breakdown?

Peck: They were nothing like I had ever seen before, or have seen since.

Playboy: Do you admit that possession sounds farfetched?

Peck: I don’t think I’m going to convert you. I was converted through personal experience. I approached it as a skeptic, too. I did not believe that possession existed. But it seemed to me that if I could see one good, old-fashioned case of possession, it might change my mind. I didn’t think that I would see one. For twelve years, I had a busy psychiatric practice and I hadn’t seen one, though for the first ten of those years, I could have walked right on top of one and not known what it was.

Playboy: But once you accept the Devil, you can explain away anything?

Peck: All I can tell you is that for a couple of years, I had been vaguely open to the idea but hadn’t seen anything to convince me. I went out looking for it. The first couple of cases of reported possession I saw were, as far as I was concerned, standard psychiatric disorders. I was very happy, believe you me. I put notches on my scientific pistol and said, “See there?” For the third case, I went to another state to interview a woman who had some features suggestive of schizophrenia, some of what we’d call flight of ideas. She also had some features of what we’d call hysteria and other traumatic disorders, but she didn’t feel quite like a hysteric. After about four hours, I was already mentally packing my bags and making my third notch on my scientific pistol when she began talking about her demons.

Playboy: Couldn’t you have explained that as more hysteria?

Peck: Well, she said that she felt sorry for them. When I asked, “Why?” she said, “Because they’re really weak, pathetic beings.” That caused me to prick up my ears. It seemed to me that if somebody had a psychiatric need to invent demons, he would invent big, strong, scary demons. Later I learned that this is a quite common demonic strategy, to portray itself as weak and frail–“No need to be afraid of me.” At the time, all I knew was that it didn’t fit. It caused me to start looking a little deeper. Then, the more time we spent, the more things came up that didn’t fit. It wasn’t so much supernatural stuff as it was stuff that just didn’t fit with who this person was.

Playboy: Yet if you had been a psychiatrist who didn’t accept the Devil, couldn’t you have explained away everything you saw?

Peck: If I’d been an ordinary psychiatrist, I would never have gotten involved with the case to begin with.

Playboy: Unless you were seriously trying to treat a person who happened to have those symptoms.

Peck: All I can tell you is that I think that genuine possession is very rare. There are certain people who see demons lurking in all corners. I think that’s irresponsible. Nonetheless, I think it is an underdiagnosed condition.

Playboy: Modern psychology tells us that we have to be responsible for our actions. If someone has made a pact with the Devil, he’s no longer responsible for his actions.

Peck: No! There is cooperation. Once I was called by a lawyer who wanted me to examine a client, a murderer, and testify on his behalf–to get him off by virtue of insanity, because he was possessed. I said, “As far as I’m concerned, whether or not your client is possessed has a great deal to do with how he would be treated in therapy, but I could not support a not-guilty verdict on the basis of insanity–because there is a choice.”

Playboy: Isn’t it likely that if possession were real, other psychiatrists throughout history would have believed in it? Even Jung, who dealt with spirituality, never considered possession.

Peck: It’s true that I am the only well-known, scientifically trained psychiatrist who has dealt with it. I know three other responsible psychiatrists around the country who have dealt with it, but they’re not the biggies.

Playboy: So you’re left in pretty shaky company, since the other people who talk about the Devil are those fundamentalist preachers who depend on ignorance and blind religious belief. They scream about possession every Sunday on TV.

Peck: It drives me bananas. On the one hand, you have people seeing possession when it doesn’t exist, and on the other hand, you have people refusing to see it when it does.

Playboy: Do you believe that there might, indeed, be satanic messages in some rock albums?

Peck: There’s a lot of satanic stuff, cults and rituals, going on, and people would rather overlook it. But it’s dangerous. Are there evil, satanic rock lyrics? Yes, there are.

Playboy: Placed there intentionally by heavy-metal Devil worshipers?

Peck: I’ve not made enough of a study of this to tell you. But when I first saw MTV, I was flabbergasted by the very clear satanic images.

Playboy: Isn’t a lot of that just posturing and attempts to shock on the part of bands? Attitude?

Peck: Whether the musicians are doing it consciously or unconsciously, I don’t know. If it’s only because it’s cool, it’s a sick way of being cool.

Playboy: Would you censor them?

Peck: We get into a terrible problem. Where do you draw the line? It’s always a question of drawing the line. For instance, I believe pornography can be healthy. Pornography can be used for good or for ill.

Playboy: Do you lump all nudity into the category of pornography?

Peck: No, I separate only the really demeaning, violent stuff. Otherwise, I think it’s natural to look at pornography. I enjoy it. But I also think that there is a tendency to demean women and to diminish and strip sexuality if its potential holiness.

Playboy: Holiness?

Peck: In The Road Less Traveled, I wrote, “When my beloved first stands before me naked, all open to my sight, there is a feeling throughout the whole of me: awe.” And I asked, “Why awe?” If sex is no more than an instinct, why don’t I simply feel horny or hungry? Such simple hunger would be sufficient to ensure the propagation of the species. Why do I feel it throughout the whole of me? Why should sex be complicated by reverence?

Playboy: Well?

Peck: To me, sex and God are inherently connected, which is why the American ideal of romantic love is so troublesome. It holds that it ought to be possible for Cinderella to ride off with her prince into an endless sunset of endless orgasms. Well, anyone who buys that is doomed to disappointment. Such people are looking to their spouse or their lover to fulfill them, to be their God, their heaven on earth. It violates the First Commandment. Idolatry of human romantic love is no less a form of idolatry.

The older I’ve gotten, the more impressed I have become by sexuality, by what the mysterious essence of the difference between men and women is, which we don’t understand. Science doesn’t even begin to understand what the nonanatomical differences between men and women are–to what extent they’re genetic, to what extent they’re cultural, and what not. But I’m profoundly impressed by the differences.

Anyway, sexuality is one of the few things that keep me humble, because it’s bigger than I am.

Playboy: You have taken some controversial stands regarding sex, such as your suggestion that fidelity is not necessarily good.

Peck: First of all, there is no such thing as a marriage that does not have to deal with the problem of fidelity or infidelity. I cannot tell you what the right way to deal with it is. The only thing I can do is tell you what the wrong way is. At one extreme is the couple who say, “What’s the problem? My wife and I have been married for thirty-five years and I’ve never even looked at another woman and she has never even looked at another man.” But that doesn’t work.

Playboy: You think that’s impossible?

Peck: The price that people have to pay for that kind of repression simply isn’t worth it. They don’t know how to deal with those feelings–it might be the Holy Spirit that’s leading you on, or it might be Satan, or it might be your glands. But it’s impossible ever to know that what you are doing is right. However, if your will is steadfastly to the good, and if you are willing to suffer fully when the good seems ambiguous, then your unconscious will always be moving in the right direction, one step ahead of your conscious mind. In other words, you will do the right thing. But you will not have the luxury of knowing it at the time that you’re doing it.

Listen, one of our myths is that we should be completely happy with and fulfilled by one woman or one man and that the issue of fidelity should never be a problem, and that we should have no need to do such things as look at pornography. That’s nonsense. As I say in a lecture I give, sex is a problem for everyone–children, adolescents, young adults, middle-aged adults, elderly adults, celibates, married people, single people, straight people, gay people–everyone. If this is celestial boot camp, it is replete with obstacle courses, almost fiendishly designed for our learning. The one most fiendishly designed is sex. God built into us this feeling that we can max sex.

Playboy: Max sex?

Peck: Yes, that we can conquer it or solve it. Maybe we find someone for a day or two or even a year or two, but then she changes or he changes or we change and we realize that we haven’t maxed it at all. We either try again with someone else or go forward and learn about love and intimacy and how to whittle away at our narcissism, and some of us graduate from boot camp.

Playboy: Are you a graduate?

Peck: [Shrugs] With almost everything, I’m very much like the professor of philosophy who was asked, “So you believe that the core of all truth is paradox. Is that correct?” His answer was, “Well, yes and no.” There are only two great truths I know that are not paradoxes. One is that the only way to stop a game is to stop it. Eric Berne, in Games People Play, essentially defines a psychological game as repetitive interaction in which there is an unspoken payoff. Whether it’s Monopoly or the arms race or games in your marriage or the self-destructive tendencies you live with, the only way to stop a game is to stop it. The other truth? It’s a simple one: Love makes the world go round.

#

“There is no such thing as a marriage that does not have to deal with the problem of fidelity or infidelity. One of our myths is that we should be completely happy and fulfilled by one woman or one man. That’s nonsense.”

“I believe pornography can be healthy. It’s natural to look at pornography. I enjoy it. I separate only the really demeaning, violent stuff. But where do you draw the line? It’s always a question of drawing the line.”

“I get opposition from right-wing Catholics, from the New Age people and from the fundamentalists. They say that I’m the Antichrist. That’s real power–I mean, not one of the antichrists, but the Antichrist.”